Hello there 👋 Disability studies has long argued for centring lived experience. But it can be hard to fully convey what it feels like to move through a city in a wheelchair. This newsletter describes an experiment in making the invisible visible and what it revealed about surfaces designed for some bodies but not others.

The core idea was to measure vibrations on different surfaces by attaching an iPhone to my wheelchair. We wanted to capture a first-person perspective of someone traversing a city riddled with cobblestones and other dangers.

The Setup

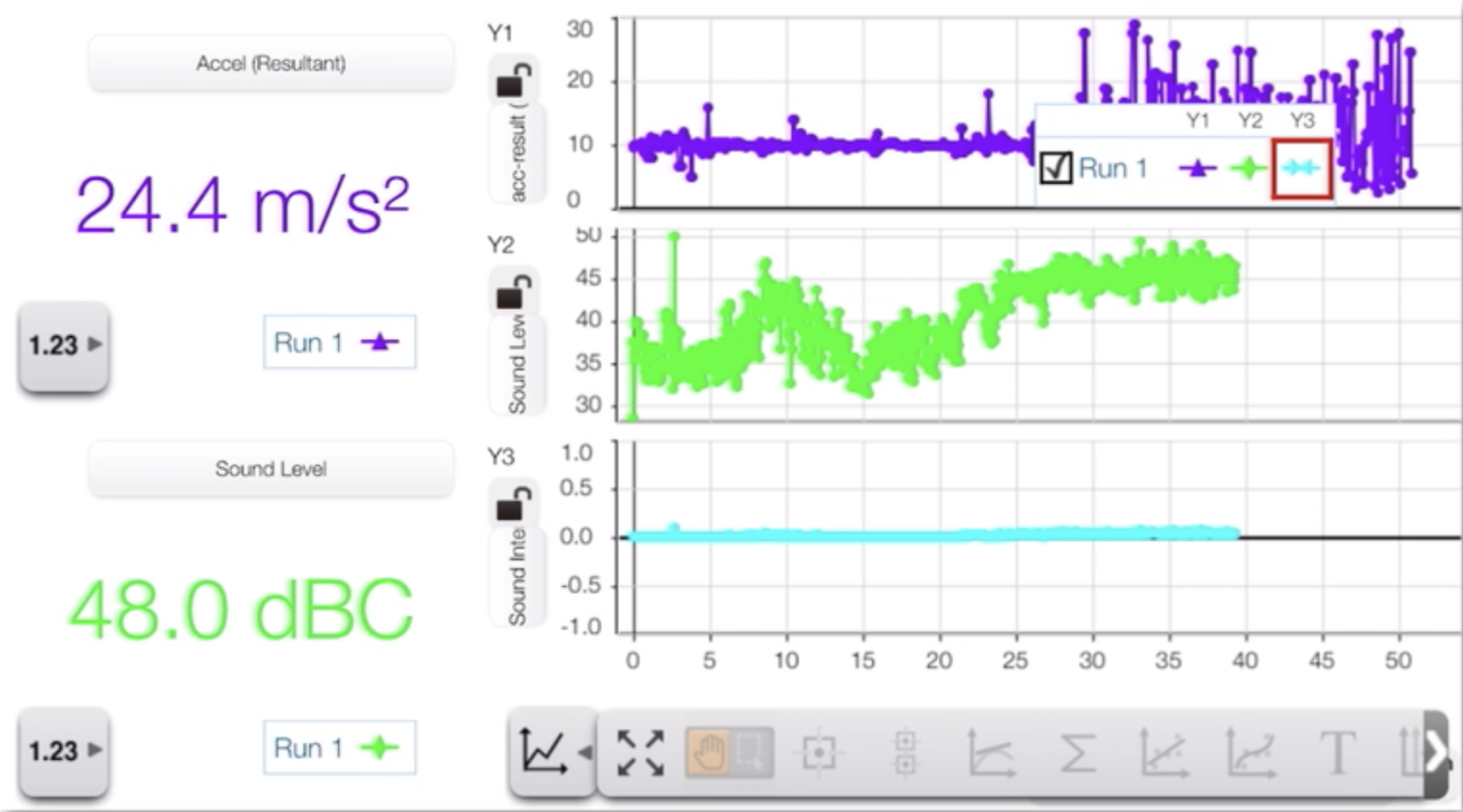

To do this, we used our smartphones, which are surprisingly powerful sensor packages with tools for measuring movement, sound, and vibration.

This was the setup:

- We used an app called SparkVue by Pasco Scientific (Figure 1). It can measure vibrations, sound, and a lot more.

- The phone was attached using Velcro, close to one of the small front wheels of my wheelchair. We also tried the same on a walker and on a rollerbag, which was quite interesting because of how much noise they made.

- We used an Insta360 camera to capture the full view, including sound. This created a “bubble,” capturing images, sounds, and vibrations.

The Surprise

After just a few minutes, we got a surprise.

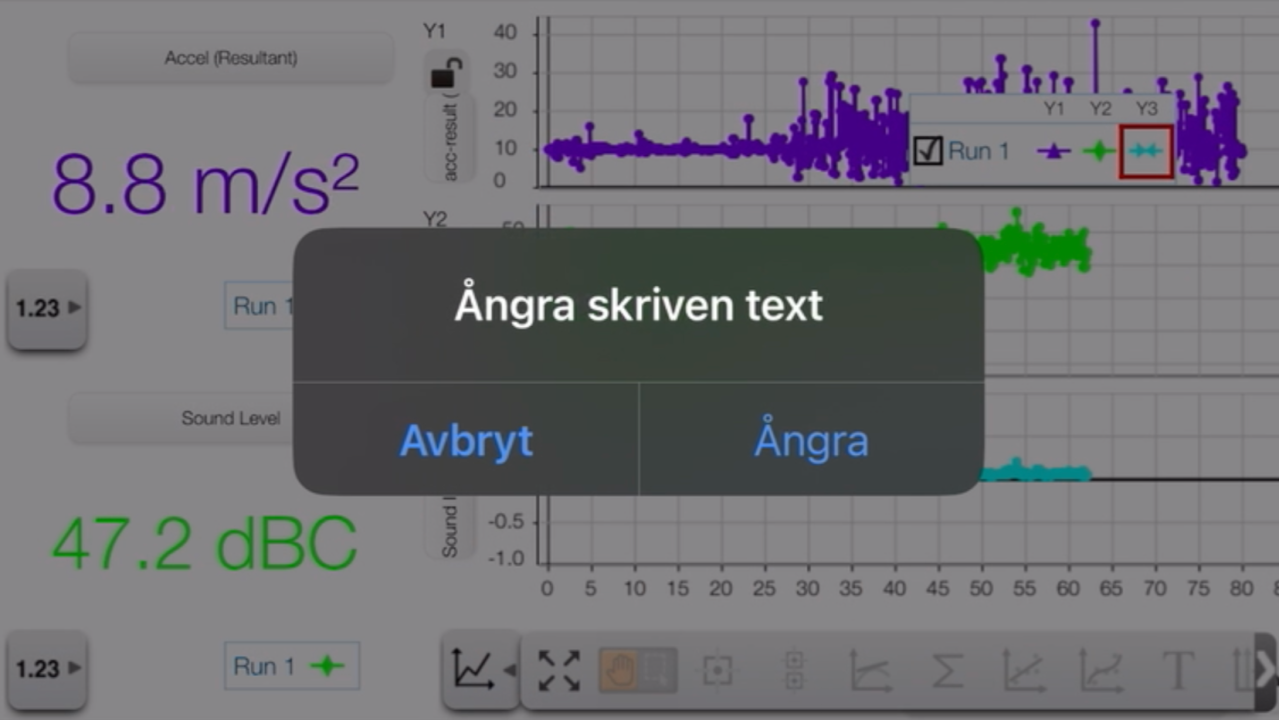

The vibrations picked up by my phone were actually so powerful that they activated the "Shake to Undo" feature. If you have ever tried it, you know you actually need to shake your phone quite heavily to activate this function.

Since we recorded the screen, the app got covered by the "Shake to Undo" prompt (Abort or Undo).

This wasn't exactly what we had expected, but it actually turned out to be quite a powerful illustration of how intense the vibrations were. Sometimes, this can be hard to convey, which was one of the main reasons why we wanted to conduct the experiment from the beginning.

The Lived Impact

This experiment demonstrates what disability studies has long argued: that lived experience must be centred.

Yet words alone often fail to capture what it means to traverse a city in a wheelchair, and to have your belonging denied by the very ground you move on:

- What the vibrations do to your body.

- How the rattling sounds make it hard to communicate with your partners, especially if they are walking upright.

- The number of signs you miss because you need to concentrate on the immediate ground before you, and still risk getting stuck in a crack and falling.

- The feelings of insecurity and the work the surface imposes on you, what Bonehill et al. call emotional work [1].

These aren't minor inconveniences. They are design choices. Choices that systematically produce inequality by assuming certain bodies and excluding others. The vibrations aren't unfortunate side effects of historic cobblestones; they're the continuing impact of surfaces designed for walking feet, not rolling wheels.

The "Shake to Undo" prompt is just accidental poetry: the phone is trying to undo what just happened because it's so violent it must be a mistake. But it's not a mistake. It's designed cobblestones, chosen materials, accepted standards, normalised harms.

If you’re using a wheelchair, cobblestones aren’t stepping stones, that’s for sure. This is what the conditional access paradigm looks like at street level:

Do, or do not, there is no undo.

Your Turn

Want to try this experiment yourself? The setup is straightforward: download SparkVue by Pasco Scientific, mount your phone near the wheels of a wheelchair, walker, or stroller, and record what happens on different surfaces. Please tell me if you try it and what you learn.

Thank you for commenting and sharing. Let’s keep this discussion going 😊

Notes and References

This piece builds on findings from The Syntax of Equality project, where we investigate situation-based categorisation and nonclusive design through citizen science and field observations.

My aim with Nonclusive by Design is to contribute to the dialogue on how we can create environments, products, and systems that respect human difference by designing beyond “us” and “them”, without reducing people to categories. Subscribe above to receive future editions and join the conversation.

Do you want to use the photos or illustrations in a publication, presentation, or video? Go ahead, and please tell me how you use them. I appreciate attribution in some form, i.e., that you tell where you got the material from ("Per-Olof Hedvall"), but it is not mandatory 👍

References

- Bonehill, J., von Benzon, N., & Shaw, J. (2020). ‘The shops were only made for people who could walk’: Impairment, barriers and autonomy in the mobility of adults with Cerebral Palsy in urban England. Mobilities, 15(3), 341–361. https://doi.org/10/gg3j5k

Guide: Quick Setup

Here is the quick setup, if you want to try it:

- Get the app: Download SparkVue by Pasco Scientific.

- Select sensors: “Build new experiment” (Top menu option) → Choose “Sensor Data” (Button in the middle of the screen) → Choose the “On-board Acceleration Sensor” → Choose Acceleration resultant or X-Y-Z axes, and pick a graph style.

- Mount the phone: Use Velcro or a sturdy mount to attach it to a wheelchair, walker, or stroller—as close to the front wheels or axle as possible.

- Record: Hit “Start” in SparkVue and traverse different surfaces. Use the phone’s screen-recording features to record a video of your screen.

- Optional: Record video as well, for instance, on a GoPro or Insta360 camera. This way, you can follow what happens over time, and even sync it to the screen-recording.